Fantasy-themed trading cards are nothing new, but trading card games weren’t really a thing until 1993. There were a few early outliers and TCG-like games, but some argue that the release of Magic : The Gathering was the true beginning of the TCG/CCG genre. But around the same time, we also got Battle Cards by Steve Jackson and Merlin Publishing, and while the two games couldn’t be more different in their gameplay, they definitely ran in the same fantasy-themed crowds that riffed on Dungeons & Dragons. Today, Battle Cards are pretty much forgotten, but they’re one of the coolest relics of the early TCG world. Wikipedia doesn’t even mention them, and it’s a pretty big oversight.

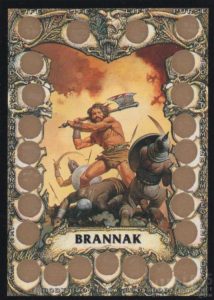

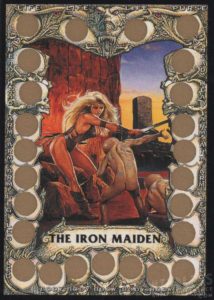

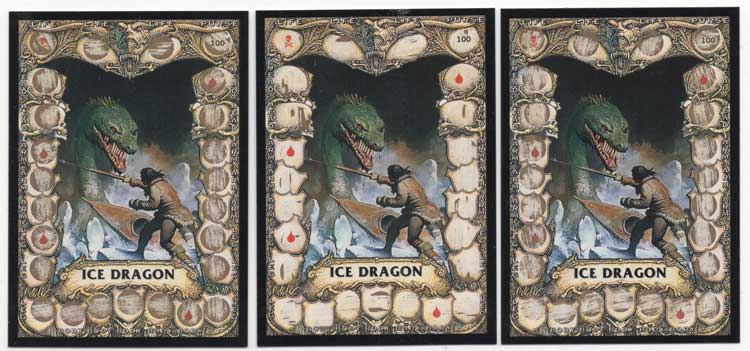

The basic idea is pretty simple. Most Battle Cards have a series of lottery-like scratch-off spots, and by scratching off the right ones in the right situations, you can win or lose a battle against your opponent’s card. Sweep up the table and repeat. It’s not dissimilar from 1989’s Nintendo Trading cards, which made you scratch off the right boxes to proceed through the terrain of a card and beat a level in Zelda, or attack right right spots on King Hippo in Punch-Out!!, or if you want to go back even further, 1985’s Robot Wars.

Battle Cards are more competitive in nature, and have to be pitted against an opponent, though you could probably devise a solo campaign if you really wanted to. Non-fighting cards effect gameplay by casting spells, diverting into other side games, or causing other similar effects. With 140 cards in the set, the variety is pretty huge. But Battle Cards go a lot deeper than these one-on-one scratch-off wars.

Playing through this, it seems like memorization would effectively ruin the game, since you’ll always know which spot to scratch off to strike your opponent, if you can just remember what the card’s pattern is, or you’ll always be able to successfully cast a spell by scratching the right spot — but this is written into the game in two very cool ways. If you’re using spells, it stands to reason that a “more experienced” spellcaster would know how to cast an effective spell with less guesswork or room for error, making memorization in the real world a known gameplay advantage, which also fits in with the very D&D-like narrative that spellcasters need to study and memorize spells in-game before they can use them.

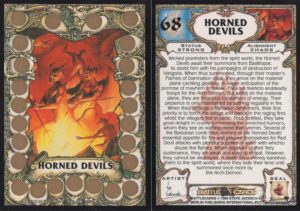

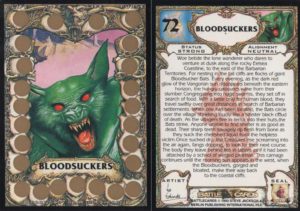

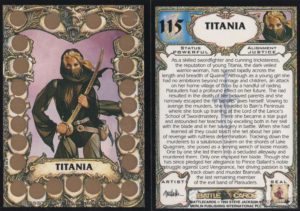

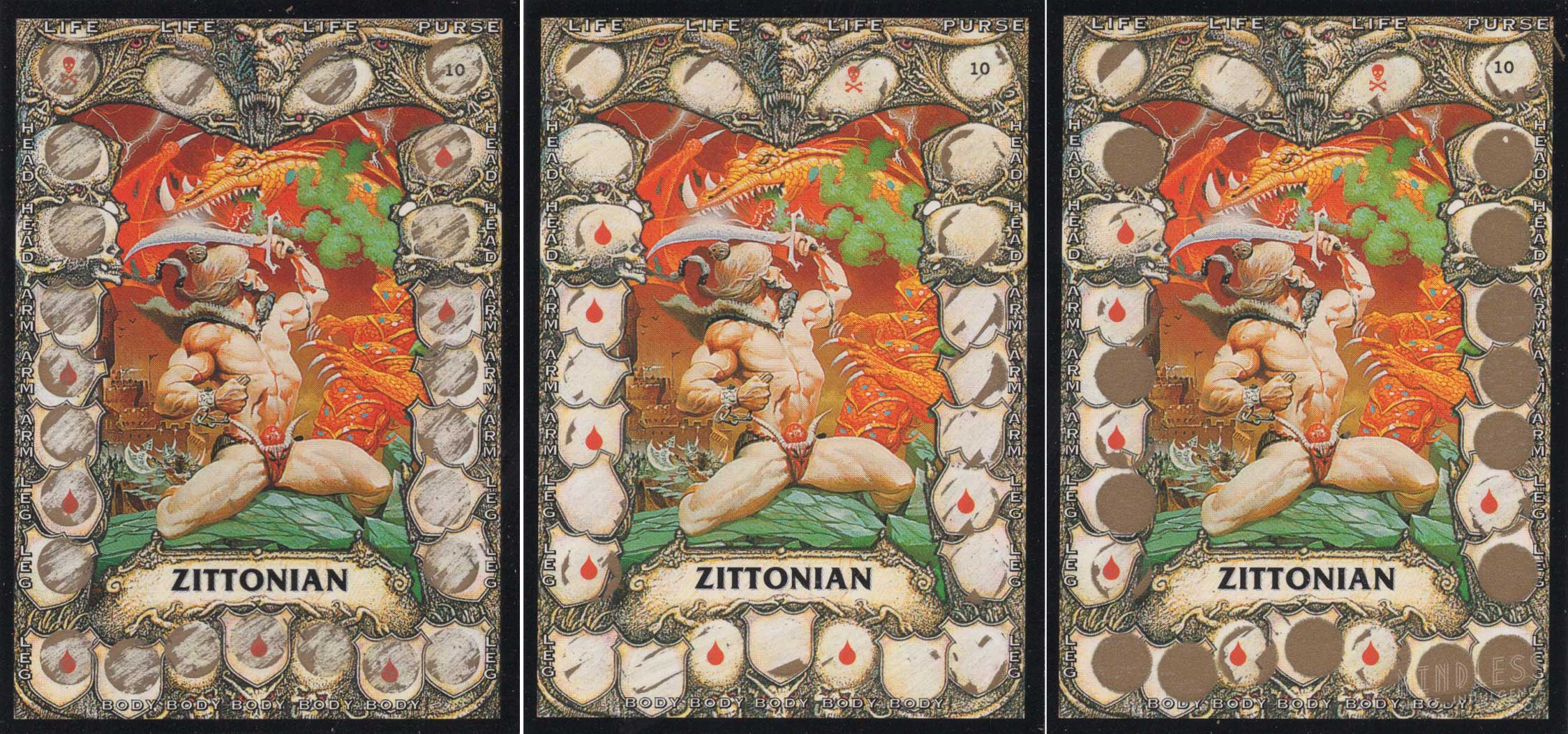

A second way this repetition is written in (or out, in this case) is with ‘Warrior’ cards. Each fighting card has a status printed on the reverse, saying things like ‘Awesome’, or ‘Strong’, or ‘Powerful’, and each of these has an in-game meaning you can discern; part of the game is decoding the best way to play, based on both personal experience and reading the complex cardbacks. As revealed on the back of one of the cards, ‘Warrior’ cards are cards where the ‘hit’ spots aren’t always in the same place, so memorization won’t always help you, as you never know which variation of the card you’re up against. Sure, you can detect a pattern after you scratch off a few, if you have an outstanding memory, but just like spellcasters, it’s reasonable to believe that a warrior would be better at evading attack, so the spots where he can be damaged will move around. It’s kinda genius, and a pretty clever way of keeping the game interesting, and limited within a reasonable narrative.

But it gets better. You’re scratching off a bunch of cards, effectively ruining their collectible value. Maybe this is why this was never defined as the first ‘CCG’, since you can’t really collect that which you destroy with a single use. What’s left when every card is basically Chaos Confetti?

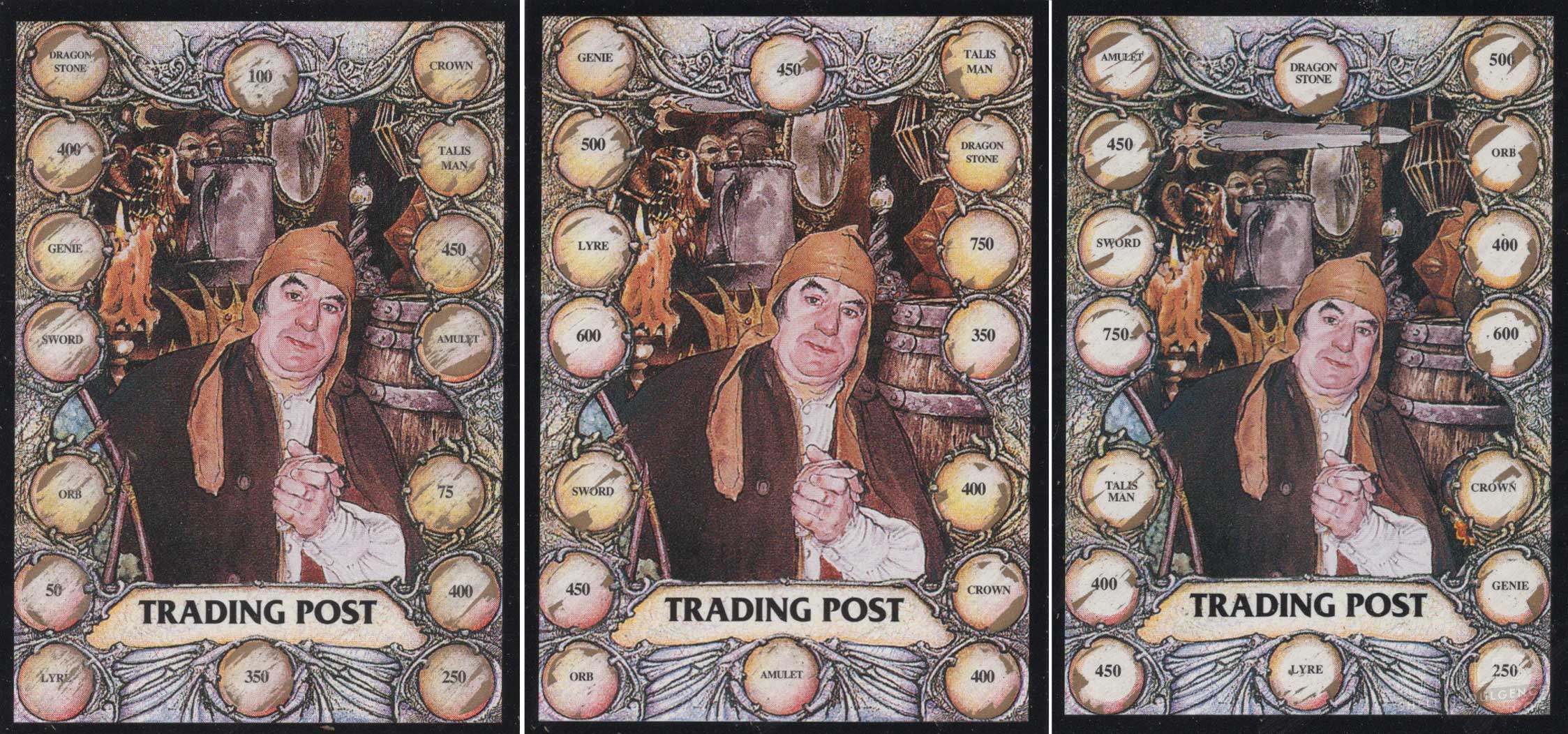

How do you convince people to scratch up their collectible cards? By offering better, more collectible cards in their place, all for the low price of a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Each Battle Card you defeat has a ‘Purse’ value, and by defeating enough of your enemies and collecting their cards, you earn money. That money can be traded in using a very common ‘Trading Post’ card, which also had to be scratched to be used properly, and features an image of Monty Python’s Terry Jones, for some reason.

In order to be able to purchase a treasure, you have to scratch off the name of a treasure, a price, and also be able to pay the price for the item. If you scratch wrong, you’re out; the card is wasted, but they’re so common, it’s hardly a loss. Like Warrior cards, Trading Post cards have a lot of variety. While you can recognize some patterns, they can also be deceiving. What’s more interesting is that there are at least four very subtly different Trading Post cards, all framed a little differently by a millimeter or two. Two art variations are seen above, as well as three different scratch patterns.

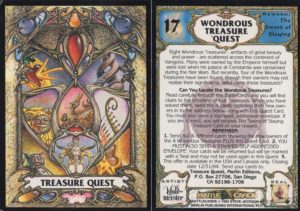

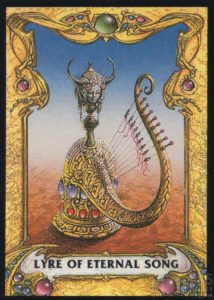

But it gets better. The tertiary value of the cards goes deeper, and that’s by solving the mysteries and puzzles that span the narrative of the cards. Many of these contain what might easily be seen as an overwhelming amount of information: stories from the land of Vangoria, runic writing, strange symbols and riddles, as well as unique gameplay instructions for specific cards. A number of Quest cards ask you to solve puzzles by identifying a subset of cards; there are five cards that have a Where’s Waldo-type search for an image of a ring, while others ask you to find a specific ‘Jester’ symbol hidden on some cards. Others require IDing cards based on knowledge of the game’s story, and by sending in these cards (again, free of charge except for a SASE, and stamps were 24 cents in 1993), you’d earn better cards. And if you invested your time and stamps, you’d be well-rewarded today; by redeeming a bunch of rare cards, you could get a gold foil ‘Emperor of Vangoria’ card, worth over $900 today. Even standard gold foil mail-away cards can go for $75, but don’t get excited about buying a box of these and hoping to find any. A base set of 140 cards has sold for as little as a dollar as of early 2022, though the eight yellow-edged ‘Treasure’ cards go for a little more. Like so many things, the real money was in being there before 1994, and getting involved.

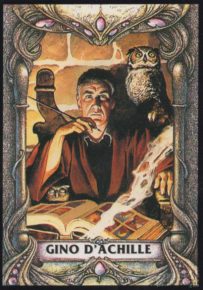

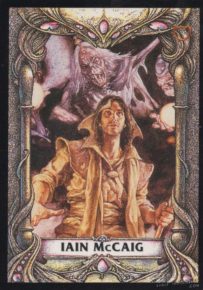

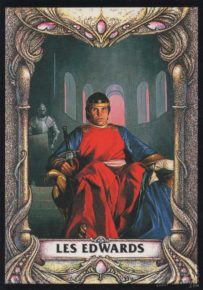

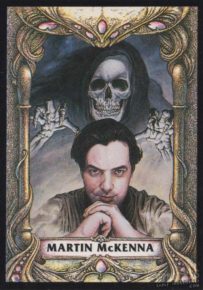

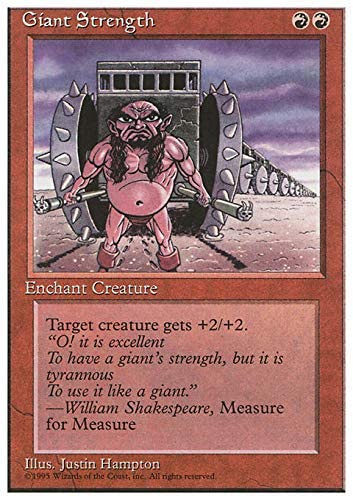

Battle Cards had some of the best original fantasy art of the time, and they knew it. Compare these to some of the Magic art at the time, which was charming, but pretty rough at times.

I get it. I’ve done some pretty bad art that I regret. It’s also very understandable when the art went wrong; these were very young companies on a budget, and 95% of this stuff was still better than some really awkward Monster Manual moments.

A subset of Battle Cards highlighted each artist involved, and each one is pretty incredible. Each one is a master of fantasy art. It took me a while to realize that artist Iain McCaig, whose work is exceptional here, is also responsible for one of my favorite album covers of all time, Jethro Tull’s weirdo new-wavey synth-folk Broadsword and the Beast.

Gino D’Achille is someone I’d been seeing for years, adorning many collections of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter books, as well as some other sci-fi/fantasy classics, which is another active collection I pursue.

Les Edwards entered my life similarly, as well as Terry Oakes; I could probably dig into my sci-fi stacks right now and pull out a handful of their covers.

And here’s another card mystery : the only use of ‘Waldmeister’ I can find relates to this artist’s card, and isn’t repeated by this artist anywhere else. The card’s reverse mentions his heavy involvement in The Neverending Story II, which implies that he might be Ludwig Angerer, but that’s complicated by the fact that there are a few artistic Ludwig Angerers, one has a brother named Walter, aka Angerer the Younger, who is a sculptor. It’s not clear at all how any of these relates, and it seems like nobody has bothered to solve this puzzle, or the answer is so obvious, nobody’s ever written it down. Digging deeper, I’ve found the answer, and it’s just one of the thrilling deep dives these cards provide, even today.

The creature designer on The Neverending Story II was a man named Patrick Woodroffe, who passed away in 2014. ‘Waldmeister’ is an alternate name for woodruff, a small, flowering plant. Visiting Woodroffe’s website, it becomes clear that this is the artist behind these cards, and both this card and his Wikipedia entry confirm his birthplace of Halifax and education in Leeds. Consider this one solved. Unfortunately, he’s not the only one of the 7 US edition artists who has passed away.

Martin McKenna took his own life in 2020. This memorial post goes over some of his creative history.

The UK editions of the cards used art by Alan Craddock instead of McKenna, but since this focuses on the US release, I can’t say too much about him, other than like everyone else, his art is incredible, and an amazing score for such an experimental game. Many of these artists had been working with Steve Jackson games for years at this point.

Though not useable in battle, these cards too have value; some solve puzzles or complete quests, and all of them can be used to figure out a set of mystery cards whose artists are left a mystery, thus winning another prize. Look at the cards above to spot two of the five aforementioned rings.

Near the end of their life in the mid-90s, KayBee Toys was clearancing out entire boxes for a buck. I found mine at the Elephant’s Trunk flea market in the 2010s, and I got them for a steep discount because the entire market was caught in a sudden torrential rainstorm that basically destroyed everything that was laid out. I bought 5 boxes that were dripping wet, crossing my fingers that the packs were water-tight, and lucked out. Fortunately, the cards can still be scratched today, as the little gold scratch-off pads haven’t fused with the cards. Some scratch easier than others, but every card I’ve scratched out of these thousands has been useable.

Battle Cards weren’t the first to embrace scratch-off gameplay; Topps had been doing it on baseball cards as early as 1970, but these were a very interesting merging of ideas, and executed at the very peak of what could be done with trading cards of the pre-internet era. They invite a kind of exploration and interactivity that’s not so much lost today, but significantly shifted. Instead of trying to discover a point of information in a curated, reliable source, Web 2.0 insists that we sift through mountains of misinformation and advertisements to access the information we want. But here, almost everything you need to know is confined to a stack of trading cards, and the postal service, and maybe interacting with other collectors. It’s organic, from the exploration to the physical action of scratching off the cards. It’s unique, and would be difficult to replicate today.

As I explored these, I did no research on how to solve these puzzles (except for the not-so-official puzzle of Waldmeister). I didn’t look for a legend to the runic alphabet, or where to find the Jester’s symbols — I still haven’t been able to find a single one. I don’t know the name of the Princess’ suitor. I don’t want to know.; I want these to be as close to the 1993 experience as possible. Would Steve Jackson Games respond if I sent in the solution to one of these puzzles 23 years later? I doubt it, but I think I’ll try. God knows I have a few thousand now, and more than enough envelopes.

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.