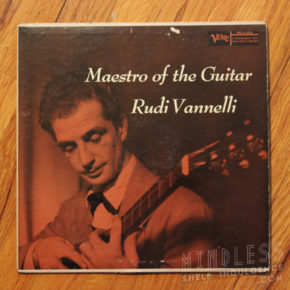

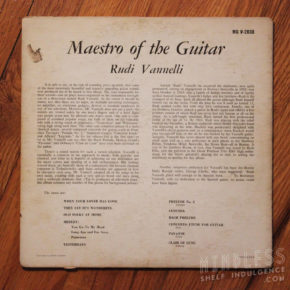

Virtuoso guitarist Rudi Vannelli died in 1961 of a heart attack, five years after he released his one and only album on Verve Records, 11 tracks under the title Maestro of the Guitar. Aside from census records, a single album review, a few performance notices, and Verve’s own recording schedule, it’s the only public evidence that he ever existed.

In the late 2000s, I found Rudi Vannelli’s only album in a dumpster outside of the library where I worked. It was a couple of layers down, under strata of unwanted Christmas records and classical albums and crooners, so it had stayed dry despite the rain that day. The library always received donations of records, but because of limited space, most of the employees just took it upon themselves to just chuck them in the trash, but I’d try to salvage a few good ones from the piles.

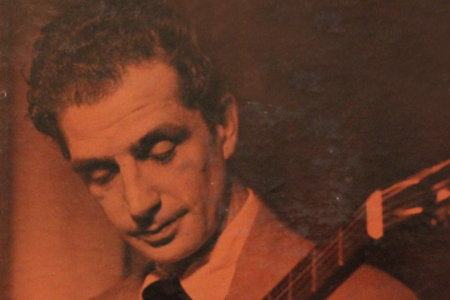

Something about Maestro of the Guitar was special; the cover featured a sepia-toned, Vincent Price-looking guy holding a guitar, who had a name I’d never heard, and it was from a time I was born decades too late to experience. I’m not usually too interested in finding things I already know about; I’m really digging through rummage sale bins to discover mysteries that nobody really knew were mysteries yet. And Rudi Vannelli was a mystery. No amount of searching through records, on or offline, revealed much.

Rudi Vannelli was a discovery from the moment I put it on the turntable. It’s a little Django Reinhardt, and a lot of gentle, sweeping, meticulously played guitar. The album features jazzy standards, classical pieces interpreted for guitar quite possibly for the first time (according to the album’s liner notes), and other songs from musicals that feel familiar and new at the same time. It’s gentle, peaceful stuff. So who was the man behind this?

Years ago, sometime in the early 2000s, I’d written a now-lost blog post about finding this record, and how much it meant to me, and just how little information was available about the life of Rudi. Before long, his friends and family were reaching out to say hello, and thank you for noticing Rudi. Before all of those emails were lost due to a technical error, I was able to scrape together some basic biographical information :

His birth name was Adolph Vannelli, according to the 1940 census. At the time of the census, he had three brothers, and later, the family would add fourth. Rudi lived in North End of Boston, at 14 Unity Street with his family, and over the course of his life, had three wives. He died just after the death of his third child, with his third wife, Elizabeth, who also went by ‘Lisa’. He studied under master guitarist Andres Segovia, who would teach him whenever he passed through Boston. On April 6th, 1956, Rudi recorded his entire album in one recording session for Verve. In April 1957, Billboard reviewed his album (spelling his name wrong), saying that it had “artistic merit”, and that it was “good mood music and deserves airing as such,” although they also predicted miserable sales due to a lack of interest in the style of music at that time. History tells us that they were not wrong; Mr. Vannelli seemed to be a man outside of his time, but committed to his art. By contrast, 1957’s top albums included three Elvis albums, and the soundtrack to Around the World in 80 Days, with diversions into Harry Belafonte and Nat King Cole.

In 1958, Rudi played at a local coffeehouse, Mount Auburn 47 (later Club 47 and later, just called Passim), in Cambridge, three nights a week. At some point around this time, he was also playing the Turk’s Head coffeehouse. In December 1959, he was playing at The Ashgrove in Melrose, CA – a brief trip away from his beloved Boston. He died young, And that’s all I knew; most of it from personal emails.

You can listen to his full album below.

It was a huge stroke of luck that I was able to connect with Marcia Flammonde, an artist living in Pennsylvania who was living in Boston while Rudi played there frequently, and knew him personally. They met while he was on stage in a Boston club on Charles Street; Marcia and her friend were talking while he played, and it made him furious. That led to a friendship that lasted until his death at age 41; Rudi had survived a heart attack, and requested that Marcia bring him his pressed suit so that he could leave the hospital looking proper; she could not make the trip as she was in the middle of a move, and he did not have a car. He died a little while later, having never spoken to her again. It was a poetic cycle; a dear friendship that began and ended in anger, but bore no prolonged hard feelings. Rudi was a passionate guy who could easily be forgiven for his moments of anger.

When Marcia attended his funeral, she recalled that a cloth, bearing a large cross, was pulled from his casket as it moved through the church. His friends later agreed that Rudi, as an atheist, would have wanted it that way.

He’s recalled as a passionate man who loved wine, women and song; he’d more than once been asked to leave Marcia’s apartment by her husband, after Rudi became a bit too inebriated, though none of his actions were remembered as undignified, just boisterous. Rudi’s mother, an oldschool Italian woman who was born in Italy, made bathtub wine that could “blow the top of your head off”. Whether it was the product of the powerful wine or not, Rudi was never sad. “He was always delighted with things,” recalled Marcia.

But despite their friendship, and his openness, (his tendency to elaborately describe the ways in which he’d make love to his new, very young wife was noted), he didn’t speak much about his past; even those who knew him only seemed to know him in the present. And there was a lot of Rudi to talk about in the present, so presumably, nobody asked much about the past.

Rudi’s last wife just before he passed, Elizabeth, confirmed that Rudi was a man who lived exuberantly in the present, describing him, in the most positive sense, as “totally Italian”. They married at 11PM one night before a Justice of the Peace, after he’d suddenly proposed. She never knew much about his past wives or children either; and they too met while he was performing in Boston, herself a recent transplant from Greenwich Village in NY. They had been married for about a year and a half. and had one son, Andre, when Rudi died.

Rudi was connected to some of the greatest musicians in history; in addition to studying with Segovia, he was friends with cellist Pablo Casals; they’d meet at the airport when he came into town. Vannelli himself was no stranger to bowed instruments; he’d originally played the violin before transitioning to the guitar. They could have toured together, but Rudi wanted to stay home, where he’d found his joy. Or where he’d built his joy. Or both. He also almost went on to perform with singer Anita O’Day very shortly before his death. The dates were cancelled, and he was relieved; the life he had in Boston was everything he ever wanted. When he wasn’t on stage, he played outside in the North End of Boston, in a small concrete park that he called ‘The Prado’, a place where old men played chess.

He did not seek fame or traditional fortune; his fortune was his friends, his family, and his music. And though he died before he was able to record more music, he was not unhappy. His local, relatively unknown career was never a failure of any kind, but exactly what he wanted: a success of art that also paid all of his bills, even as he chased fame away. He made up his own measurement for joy and success, and by all accounts, fulfilled it with every fiber of his being.

If you knew Rudi Vannelli, or have any recollections you’d like to add to this page, please e-mail via the About page.

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.

Comments are closed.